Running experiments with small sample size

Tl;dr

I discuss:

- How to run experiments with “small” sample sizes

- What the “minimum detectable effect” (MDE) really means

- Whether the “alternative hypothesis” for an A/B test really matters

- The “prior sensitivity” of small sample size experiments

- The “false discovery rate” for these experiments, and how to reduce it

Introduction

We never have as much sample size as we’d like, but oftentimes we also have less than we need. In such small sample size situations, we aren’t able to run an adequately powered test (e.g., at 80% power) for our desired effect size. (This is usually because exposures accumulate slowly, and collecting enough exposures would take months or years.) What should we do?

There are essentially three options:

-

Don’t run an A/B test. Sometimes this means eschewing measurement altogether, but more often it means doing measurement in a less rigorous (or completely unrigorous) way. Your stakeholder might ask, “can’t we just launch the treatment and figure out its impact by comparing metrics before and after?” (This is usually called a “pre-post” analysis.). In these cases, I find it useful to remember the baseball analyst Bill James’s admonition: “the alternative to good statistics is not no statistics, it’s bad statistics”.

-

Concede lower power. Instead of running our test with 80% power, we run it with 50%, or 20%, or 10%. There are well-known problems with underpowered A/B tests, some of which I’ve discussed elsewhere on this blog. In brief, we run into two problems:

- Type II error: The probability of detecting an effect, if it exists, is much less (this is the definition of power). In other words, even if an effect exists, after running the experiment we might find no statistically significant movement in the metric of interest. This is obviously a waste of time and money. The probability that this happens is known as the type II error, which is 1 - power. For underpowered tests, this can be 50% or more.

- Type S/Type M errors. Even if we find a statistically significant result, the effect size might be greatly exaggerated (”type M (magnitude) error”) or possibly even incorrect in sign (”type S (sign) error”). These errors worsen as power decreases, and can be quite large for <50% power experiments. The first phenomenon, of magnitude exaggeration, is also known as the “winner’s curse”.

As such, Ron Kohavi argues that “Experiments with Low Statistical Power are NOT Trustworthy”.

-

We accept a larger minimum detectable effect (MDE). The third and final option is to accept a larger MDE. We acknowledge that we won’t be able to detect smaller (but still practically meaningful) effects, only “large” ones.

That these are the only three options becomes obvious when using a sample size calculator (e.g., Evan Miller’s). There are a few tweak-able parameters: the power, the MDE, and the acceptable type I error rate (alpha). (Other values, such as the mean and variance of the metric of interest, are fixed by the historical data for the metric.) Assuming we don’t want to compromise on alpha, this leaves only the power and the MDE with which to fiddle. We can either dial down power (option 2), dial up the MDE (option 3), or throw our hands up (option 1).

What does “MDE” really mean?

I’ve always been slightly confused by the multiple meanings/usages of “MDE” (particularly for sample sizing).

Sometimes, MDE refers to the smallest effect of practical interest. Here’s Kohavi et al. from Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments

For example, you could miss detecting a difference of 0.1% in revenue and that’s fine, but a drop of 1% revenue is not fine. In this case, 0.1% is not practically significant while 1% is. To estimate the required minimum sample size, use the smallest δ that is practically significant (also called the minimum detectable effect).

Sometimes, though, MDE refers to the smallest effect we can detect (as the name “MDE” would suggest). For example, Kohavi also writes (on LinkedIn)

If you ask me what MDE I want for the experiment? I want 0.1%. In reality, unless you’re running one of the biggest sites in the world, you can’t get that—you don’t have enough users!

It therefore makes sense to use the power formula in reverse…Estimate n based on historical data (fancy term for number of users in the last two weeks). Plug in σ based on that historical data and get the MDE. That’s the minimum detectable effect you could detect with 80% probability. Most of the time the MDE will be bigger than what you really want, but until you grow and have more users, that’s what you’ll have to settle for.

(There are yet other ways to determine an MDE — for example, based on past effect sizes observed in previous research in the same area. See this chapter from Daniel Lakens’s book Improving Your Statistical Inferences.)

The “smallest practical effect” and the “minimum detectable effect” aren’t at all alike, though! The former is a fixed input to the sample size calculation; the latter is an output (as implied by Kohavi’s suggestion to “use the power formula in reverse”). If the effect size is a fixed input, and we have insufficient sample size, we are forced into option 2 (”concede lower power”). But, if the effect size is a variable parameter or output, then option 3 (”accept a larger MDE”) becomes viable.

We are interested in the case where the smallest practical effect — let’s call it “SPE” — is less (perhaps much less) than the minimum detectable effect (MDE) produced by a sample size calculation. In option 2, we take MDE = SPE, and accept less power. In option 3, we take MDE > SPE (holding power fixed, say at 80%), and accept that we can’t effects on the order of SPE.

Do options 2 and 3 differ?

You might have noticed one very strange thing. There’s hardly any practical difference between options 2 and 3.

In the jargon of frequentist testing, options 2 and 3 use different “alternative hypotheses”. Option 2 takes the alternative hypothesis as \( H_a: \delta = SPE \), where \( \delta \) is the effect. Option 2 instead uses \( H_a: \delta = MDE > SPE \). These different alternative hypotheses, in conjunction with the pre-experiment power calculation, imply different values of MDE and power. They reflect different attitudes towards A/B testing when the sample size is a hard constraint.

But, in practice, such “attitudes” do not change the results generated by typical experiment platforms: t-statistics, p-values, confidence intervals, etc. These are constructed using null hypothesis statistical testing (NHST). The alternative hypothesis plays no role whatsoever. In fact, Ronald Fisher, the originator of null hypothesis statistical testing (and, unfortunately, also a racist and eugenicist), didn’t believe in using an alternative hypothesis at all!

To put it differently, whether we choose option 2 or 3 affects how we think about the A/B test before we run it. But, once it’s in motion, the result is the same. We turn the crank, collect exposures, increment metrics, and produce p-values. Our pre-test assumptions about power and MDE aren’t encoded anywhere in this machinery.

Therefore, options 2 and 3 are seemingly equivalent, and, the same criticisms of option 2 — that we are forced to accept high errors (type II, type S, type M), and end up wasting time and money — are also true of option 3. We can’t escape bad statistics by conjuring up a larger MDE.

It is true that some quantities in A/B testing — although typically not those reported by experimentation platforms — do depend on the alternate hypothesis and/or power. These include the “false discovery rate” (% of stat-sig results that are true positives), type S and type M errors, and other numbers that are related to power. But it would be strange if choosing between option 2 and option 3 caused these to change, since the A/B test we’re running is exactly the same.

The alternative hypothesis problem

The paradox can be resolved by considering one crucial fact: we can’t choose the alternative hypothesis arbitrarily. It must bear some relationship to reality. Option 3, if taken to an extreme, loses sight of this fact.

The alternative hypothesis should be related to our a priori knowledge of the effect size, a topic I’ve written about at length (see here and here). Bayesians call this the “prior distribution” for the effect size: a probability distribution encoding our beliefs about what the effect size is, before we run the experiment. In the Bayesian framework, the data from the A/B test, combined with the prior distribution, allows us to produce the posterior distribution for the effect. This is our best knowledge of what the treatment effect is, after we run the experiment.

But the prior distribution cannot be whatever we’d like. We can’t simply assume the prior distribution extends to arbitrarily large effect sizes, for which we have 80% power. If only a 50%+ effect is detectable, this does not imply that a 50%+ effect does indeed exist. The MDE is more of a fixed input than variable output, contrary to the “use the power formula in reverse” notion.

A Bayesian framework

A Bayesian framework can shed some light on the situation. Suppose that we have a minimum detectable effect of \( MDE \), and a practically significant effect of \( SPE \). In the small sample size situation, we can’t detect the kinds of effects we’d like to, so \( SPE < MDE \). Furthermore, let’s suppose a (somewhat artificial) prior distribution for the effect size, in which we have three spikes (see figure below)

- at 0, for the null hypothesis

- at the SPE

- at the MDE

Each spike will have a probability/weight, and the weights should sum up to 1. The null hypothesis is generally quite likely (most experiments are not successful), so we’ll give it a weight of \( p(null) = 0.85 \), and distribute the remaining weight, \( p(SPE) \) and \( p(MDE) \), between the other two spikes.

Let’s investigate the “false discovery rate”, since this is usually the quantity we want to know from an A/B test. Recall that the false discovery rate is the probability we incorrectly conclude that a statistically significant result when the null is actually true.

We have

$$ p(\text{stat-sig}) = p(\text{stat-sig} | \text{null}) p(\text{null}) + p(\text{stat-sig} | SPE) p(SPE) + p(\text{stat-sig} | MDE) p(MDE) $$

We know that \( p(\text{stat-sig} | \text{null}) = \alpha \): this is the type I error rate (usually 0.05). We also know that \( p(\text{stat-sig} | MDE) = POWER_{MDE} \), which is usually 80% (again, this essentially by definition). Finally, \( p(\text{stat-sig} | SPE) = POWER_{SPE} \): the power if the effect equals SPE. Typically this is much less than \( POWER_{MDE} \).

Plugging these in, we find:

$$ p(\text{stat-sig}) = \alpha \cdot p(\text{null}) + p(SPE) POWER_{SPE} + p(MDE) POWER_{MDE} $$

and the false discovery rate is

$$ FDR = \frac{p(\text{stat-sig} | \text{null}) p(\text{null})} {p(\text{stat-sig})} = \frac{ \alpha \cdot p(null) } {\alpha \cdot p(null) + p(SPE) POWER_{SPE} + p(MDE) POWER_{MDE}} $$

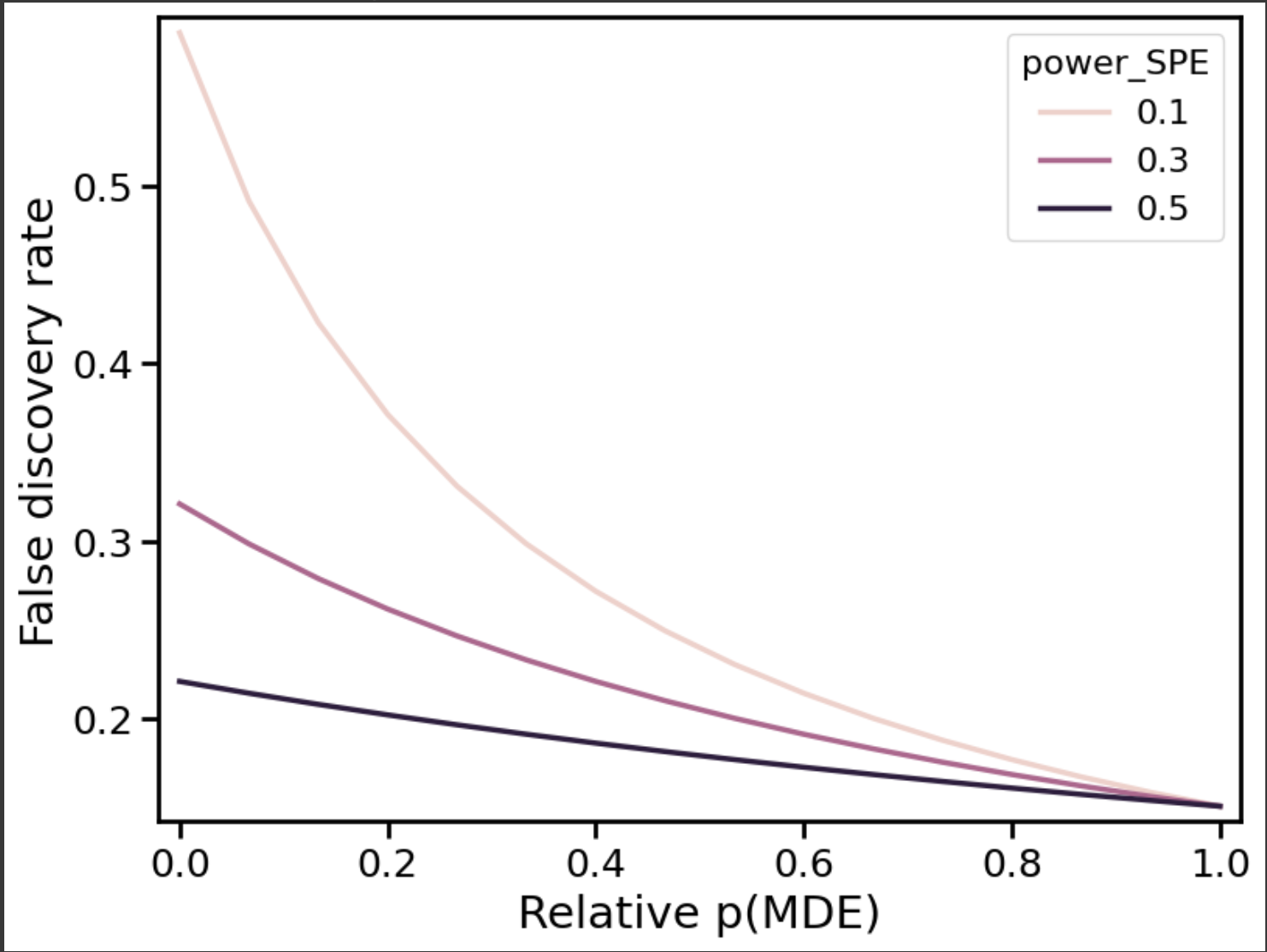

Below is a plot of the false discovery rate vs. \( p(MDE)/(p(MDE) + p(SPE)) \), for typical values of other parameters (\( POWER_{MDE} = 0.8 \), \( p(null) = 0.85 \), \( \alpha = 0.025 \) (one-sided). \( POWER_{SPE} \) is also allowed to vary between 10% and 50%.

Interpretation

A few observations:

- “Large” (detectable) effects unlikely: Suppose that observing effects on the order of the MDE is unlikely (\( p(MDE) \rightarrow 0 \). This is the leftmost part of the plot. As \( POWER_{SPE} \) decreases, the false discovery rate balloons, to over 50% (at 10% power). In this regime, the likelihood of making a false discovery — drawing the incorrect conclusion from a statistically significant result — is very high. A/B testing is not trustworthy here, as Kohavi explained.

- “Large” (detectable) effects likely: Suppose, instead, that observing effects on the order of the MDE is reasonably likely (\( p(MDE)/(p(MDE) + p(SPE)) > 0.5 \)). This is the right-hand side of the plot. In this case, the situation is much better. False discovery rates are reasonably well-bounded (less than 25%), regardless of \( POWER_{SPE} \).

To recap: If large effects are unlikely, we’re underpowered, and perhaps woefully so. This is like option 2. However, if large effects are reasonably likely, we’re no longer underpowered. In other words, “power” only really makes sense in relation to a particular effect size. An A/B test with 80% power to detect a particular effect will have much less power to detect a much smaller effect. What effect sizes are likely determines how much power we actually have.

Of course, the prior distribution of effect sizes is largely subjective, and we often don’t know the precise probabilities of different effect sizes. But here’s the main point: we can’t escape the problems of underpowered tests by making up a large MDE, as in option 3. The large MDE also has to be a priori plausible (not just possible). A (conservative) rule of thumb is that \( p(MDE) > 3 \alpha \) to keep the false discovery rate under 25%. (We get this by assuming that \( p(\text{null}) = POWER_{MDE} \), which is not unreasonable.) In words: the probability of an effect we can adequately power must be at least a few percent if \( \alpha = 0.01 \), and even larger for more typical values of \( \alpha \)).

(One note: this analysis is based on an artificial "three spike" prior. But I don’t think the essential conclusions change much if we assume a more realistic (diffuse) prior.)

Recommendations

The rule of thumb formula suggests a useful strategy for avoiding false discoveries in the small sample size regime. We simply set \( \alpha \) to a much lower value than we typically use (say, 0.01 or 0.005 instead of 0.05). We pursue option 2 (or option 3 — they’re basically the same), and, because the probability of making a type I error is so small, we can feel relatively confident that an observed stat-sig result constitutes a true positive. (Note: lowering \( \alpha \), rather than changing power, echoes advice provided by other authors.)

A different approach is to go Bayesian. But, again, we still need to specify the prior distribution for the effect size, which isn’t easy. One way of pithily summarizing this post is that experimenting with small sample sizes is hard because we don’t know the prior. If we did, we’d be able to tell, a priori, if we are underpowered or not. If the (true) MDE is reasonably likely, we have no issues. If it isn’t, we will likely waste our time and everyone else’s, since we’ll only be able to measure effects that are unattainable.

One other quantity to think about, besides the false discovery rate, is the probability of making a true discovery. In other words, what percentage of experiments will be fruitful? This is, not surprisingly, basically equal to \( p(MDE) \). If your product manager asks you to run an experiment with a small sample size, and your sample size calculation (in option 3) produces an MDE that is large and improbable, you should pause. Is it worth running a test if you are banking on a very unlikely outcome: if you expect to roll double- or triple-ones?

Of course, if the cost of experimentation is low, and experiments can be run in parallel, there is little harm in trying a bunch of low-probability ideas and seeing what works. Using a small \( \alpha \) ensures most of the resulting discoveries will be true, not false. But the fundamental problem is that, if \( p(MDE) \) itself is low, it will take a lot of experiments to even make one discovery.

To put it differently: the problem with option 2 is that power is low, and we miss out on many true effects. The problem with option 3 is different: we can feel confident in the discoveries we make, but there aren’t that many of them. But, in some sense, these are same problem.

Summary and conclusion

Running an A/B test with a “small” sample size has a well-defined technical meaning: the sample size is less than what we need to adequately power a given MDE. We have three options: don’t run an A/B test at all; run an underpowered test; or increase the MDE, and concede that only large(r) effects are detectable.

The point of this post is that options 2 and 3 are not really that different. Power is intelligible only in relation to a particular effect size, and options 2 and 3 only work if the effect size we can detect is also one that is reasonably likely to occur.

Part of the confusion stems from the polysemous nature of “MDE”. It can mean, variously: the smallest effect of practical significance; the smallest effect we can detect with adequate power in a statistical test; or the typical (or largest) effect we can reasonably expect to observe. I argue that we need to understand the latter two to assess whether we’re actually “underpowered”. We should not simply assume that large MDEs, which might be obtained by running the power calculation “in reverse”, are plausible.

Of course, we don’t necessarily know, with any precision, the prior distribution for the effect size. But our domain knowledge and prior art can help us construct a plausible prior. The prior helps inform how trustworthy the experiment is: how likely it is that a stat-sig “discovery” is true or false.

If we can detect only large effects, one useful strategy for limiting false discoveries is to reduce \( \alpha \). A rule of thumb is that the probability of observing effects equal to the MDE, or larger, should exceed \( 3 \alpha \). Another strategy is to go Bayesian. Regardless, we will have to make an assumption about the prior, and some of the experiment results (the expected false discovery rate, type S, and type M errors) are sensitive to this prior knowledge (although others, like p-values, are not).

Running small sample size experiments is not a terrible idea. But we should be realistic about what we can expect. Either we will make an intolerably high percentage of false discoveries, or (after reducing alpha, or going Bayesian) we will make hardly any discoveries, true or false, at all. If experimentation is cheap and readily parallelized, there is little harm in throwing darts at the wall, but more often this situation warrants rethinking the broader experimentation strategy altogether.