The Bayesian Euro step

Tl;dr

I discuss:

- The pros and cons of a Bayesian approach to A/B testing, versus traditional NHST testing

- How, while the Bayesian approach eliminates some difficulties with NHST, it introduces its own

- How, there are strong dependencies of some results, like the false positive error, on the width of the prior distribution

- How broad or "non-informative" priors should not be used in Bayesian A/B testing

Introduction

Null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is a notoriously tricky topic, and, even now, I find myself fumbling when trying to answer the question “what does a p-value from an A/B test really mean?”

There are two approaches to answering this question. One is to regurgitate the classical definition, something like: “if this A/B test were repeated an infinite number of times, it is the proportion of times in which we would expect to observe a result as extreme or more, provided the null hypothesis is true…”. I can feel my own eyes glazing over as I write this; I shudder to think how everyone else is feeling.

The other approach is to step around the question. We might say that p-values are not necessarily meaningful, and we should instead answer a different question. As I show below, this other kind of statistics is related to NHST but is logically distinct. It usually involves Bayesian reasoning: reasoning that uses concepts like Bayes’ theorem and combines “prior” knowledge, known before the A/B test is run, with data accumulated from the A/B test itself.

I’ll call this the “Bayesian Euro step”: a crafty piece of footwork from basketball in which you feint in one direction, and attack the basket in the other. By employing the Bayesian Euro step, we can evade our “defender”: the complications associated with traditional NHST, interpretation of p-values, and so on. We try to circumvent what one writer called “science's dirtiest secret” — the fact that the “method of testing hypotheses by statistical analysis stands on a flimsy foundation”.

Euro-stepping in basketball verges on violation: it is often difficult to distinguish between the Euro step (a legal move) and traveling (an illegal one). Similarly, the Bayesian Euro step can easily descend into illegitimate statistics. I also worry that its proponents might be overselling its advantages. Bayesian reasoning does not eliminate the problems of NHST; it only makes them more explicit.

Preliminaries

First, some preliminaries. When we run an A/B test, we collect “samples” from the treatment and control populations. The samples are subsets of the populations, and therefore any “statistics” generated from these samples will likely differ from the “parameters” of the population itself. As an example, if we compute the average height of a representative sample of New Yorkers, that number (the sample statistic) will likely differ from the true average height of New Yorkers (the population parameter). The magnitude of the difference is related to the size of the sample, per the central limit theorem. If we had infinite time and could collect an infinitely large sample (which, at that point, is the population), we wouldn’t have to bother with p-values and NHST.

We almost always want to know the difference in population means, between treatment and control populations. Let’s call this the “effect”, for short. Is the effect 0? This is the “null hypothesis”: the statement that our treatment made no difference. Or instead is the effect positive? We usually want to know whether it is positive “enough”: to outweigh the (presumed) costs of shipping and maintaining the change represented by the treatment. We typically have a "minimum detectable effect", or MDE: effects larger than this number satisfy the cost-benefit tradeoff.

Given this context, let’s try to restate, in simpler terms, what the p-value means. It is the probability of observing the difference in sample means that we actually observed (or more extreme), given the effect is actually 0 (i.e., the null hypothesis is true). At this point, you might observe a few things:

- We started with the goal of measuring the difference in population means: the “effect”. We ended with statements about the probabilities of such differences. This shift, from parameters to probabilities of parameters, is a consequence of sampling. If we could measure entire populations, life would be much easier.

- The null hypothesis is never actually true. The probability that the treatment made literally 0 difference is almost certainly 0. Instead, we should think of the “probability distribution of the effect”. If this distribution is narrow, we can make strong statements about how beneficial our change was. On the other hand, if this distribution is wide, we can make no such statements.

- The p-value is essentially the inverse of what we want. We want to know, “given the data we observed in the experiment, what is the probability distribution of the effect?”. Instead, the p-value tells us, “given the effect is 0, what is the probability of observing the data in the experiment?”

As I mentioned before, this is where the “Euro step” comes in. Instead of focusing on p-values and NHST, we measure the probability distribution of the effect.

But how?

You might remember from statistics class that “inverting” statements about probabilities requires Bayes’ theorem. This is the “Bayesian” part of the “Bayesian Euro step”. Practitioners of the Euro step will suggest applying Bayes’ theorem to statistical testing and the interpretation of p-values. For example, here’s Harlan Harris:

As I discussed previously, although in general p < 0.05 does not mean “95% likely to be better”, in the very simple case of a t test for a properly-executed A/B test with adequate power, it’s very close, and certainly adequate to mean “almost certainly better”.

Before certain statisticians in the audience write angry comments, I’m well aware that interpreting frequentist intervals correctly requires some hair-splitting language, and that Bayesian credible intervals are more directly tied to peoples’ intuitions. As it turns out, though, in practice at the scale that most web A/B tests run, there’s no practical difference. You can interpret frequentist [confidence] intervals such as the above as if they were Bayesian [credible intervals], and describe them the “wrong way”, as if they were saying something about the beliefs you should have about the true values.

Because the number of observations is high, and our prior is relatively broad, the [Bayesian credible interval] is essentially the same [as the confidence] interval as we computed above. So we’re justified in the hand-waving that makes communications with business people much, much clearer. We can defensibly say, if pressed, that “very likely” is equivalent to “a range covering 95% of the credible values of the true ratio.”

That was a bunch of jargon, some of which you might not have understood. But the basic idea is that, through some magic (Bayes’ theorem), we can generate “Bayesian credible intervals”. These are not the “confidence intervals” from traditional NHST, although they can be very similar. Bayesian credible intervals capture the distribution of the true effect. There is a 95% chance that the true effect lies within the interval. And, if the credible interval is relatively narrow (which requires an A/B test with a large sample size), we can make very strong statements. Examples are: “it is 98% likely that the effect was positive, and the treatment was better than the control” or “it is 92% likely that the estimated benefits of shipping the treatment cell are larger the costs”.

Unfortunately, in statistics as in many other disciplines, there is no free lunch. Going from typical NHST outputs (p-values and confidence intervals) to Bayesian results (credible intervals, posterior distributions of the effect) requires some assumptions. The biggest one is the prior. This embodies our prior beliefs about the effect: that is, prior to the A/B test launching. Bayesian analysis involves combining our prior beliefs with the data from the A/B test to construct a "posterior" distribution. Harlan Harris mentioned the prior in passing, saying “our prior is relatively broad”. But why? And what if that assumption doesn’t hold?

(As a slight digression, I’ll also mention another assumption, often glossed over, that is important for both NHST and Bayesian interpretation: “adequate power”. While the excerpt above mentions that this assumption is met “at the scale that most web A/B tests run”, I think this statement is too strong. An A/B test can have adequate power for some metrics (proxy metrics) but not others (business guardrails). There can be business constraints (e.g., A/B test runtime) or competing experiments that reduce sample size. And there are often other subtle considerations, like the fact that for very large companies, even very small relative effects, which are hard to power, can be materially important, and large effects become increasingly hard to generate as a product matures. I would argue many, if not most, web/tech companies struggle with power, and this problem is not confined to the social sciences, as we might like to believe.)

Monte Carlo simulations

I could walk you through a derivation of some results, but I think it’s more useful (and fun!) to brute force our way to the answer. I will employ “Monte Carlo simulations”. These can be used to obtain Bayesian quantities, such as credible intervals and the (posterior) distribution of the effect. But the same simulation can also yield the usual NHST results (p-values, confidence intervals, etc.).

Here is some code we can use to run a single Monte Carlo “trial” for an A/B test, where both the control and treatment are Gaussian distributions with a standard deviation of 1 (this can be easily adapted to other cases, like conversion rates, etc., by using different distributions, like Bernoulli).

It is all available in this Google Colab notebook, if you’d like to follow along

First, some imports

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

from scipy.stats import norm

# note: initialize random number generator upstream with

rng = np.random.default_rng()

Then, some helper functions (using standard formulas for sample size, p-values):

def p_from_z(z):

"Get p-value from z-score (two-sided test)"

return 1 - (norm.cdf(np.abs(z)) - norm.cdf(-np.abs(z)))

def gen_sample_size(effect_size, power=0.8, alpha=0.95, sigma_pooled=np.sqrt(2)):

"""Generate the sample size (per cell) required for an A/B test to be

adequately powered

effect_size: size of effect we want to be able to detect ("MDE")

power: probability of detecting true effect, assuming it exists (defaults to 80%)

alpha: probability of having a "type I error" (declaring a result is stat-sig,

even though the null hypothesis is true)

sigma_pooled: pooled standard deviation (defaults to sqrt(2), since standard deviation

of control, treatment is 1)

"""

beta = 1 - power

zcrit_alpha = norm.ppf(1 - alpha/2)

zcrit_beta = norm.ppf(1 - beta)

N = int(sigma_pooled**2 * (zcrit_alpha + zcrit_beta)**2/effect_size**2)

return N

Then, the monte carlo trial code itself:

def run_monte_carlo_trial(mu_C, mu_T, N, sigma_C = 1, sigma_T = 1):

"""

Run a monte carlo trial for an A/B test with sample size N

Both the control and treatment distributions are assumed Gaussian

with standard deviation 1, for convenience

(other distributions/parameters are possible,

but, per the Central Limit Theorem,

the results should be similar for large N)

mu_C: actual mean of control distribution

(population parameter)

mu_T: actual mean of treatment distribution

(population parameter)

N: sample size for each cell

sigma_C: standard deviation of control distribution

(population parameter), defaults to 1

sigma_T: standard deviation of treatment distribution

(population parameter), defaults to 1

"""

# run the Monte Carlo draws:

# enerate control and treatment samples

draw_C = rng.normal(loc=mu_C, scale=sigma_C, size=N)

draw_T = rng.normal(loc=mu_T, scale=sigma_T, size=N)

# compute some statistics

# use ddof = 1 to get sample standard deviation (unbiased estimator)

sigma_sample_C = np.std(draw_C, ddof=1)

sigma_sample_T = np.std(draw_T, ddof=1)

# pooled standard deviation

# note this formula is incorrect for unequal sample sizes,

# but here we have equal sample sizes by construction

sigma_sample_pooled = np.sqrt(sigma_sample_C**2 + sigma_sample_T**2)

standard_error = sigma_sample_pooled/np.sqrt(N)

mu_sample_C = np.mean(draw_C)

mu_sample_T = np.mean(draw_T)

mu_sample_diff = mu_sample_T - mu_sample_C

z_score = mu_sample_diff/standard_error

p_value = p_from_z(z_score)

return {

"z": z_score,

"p": p_value

}

Let’s try to verify this code is working properly by doing two checks.

- (Null hypothesis) Ensure that, if the null hypothesis is true, the distribution of p-values is uniform (so that, for example, there is a 5% chance that the p-value is less than 0.05

- (”Alternate hypothesis”) Ensure that, if the null hypothesis is not true, and the true effect size is the one we assumed in the sample size calculation, the probability of detecting the effect is the power

# null hypothesis check

n_trials = 10_000

results = []

N = gen_sample_size(power=0.8, alpha=0.05, effect_size=0.05)

mu_C = 1

mu_T = mu_C # since null hypothesis is true

for _ in range(n_trials):

trial_result = run_monte_carlo_trial(mu_C=mu_C, mu_T=mu_T, N=N)

results.append(trial_result)

frame_null = pd.DataFrame(results)

frame_null["p"].hist(bins=100)

The resulting histogram (see Colab notebook) is quite close to what we’d expect (uniform), and a Kolmogorov Smirnov test should confirm this.

Now, the other check:

# alternate hypothesis

n_trials = 10_000

results = []

effect_size = 0.05

mu_C = 1

mu_T = 1 + effect_size # since alternate hypothesis is true

alpha = 0.05

N = gen_sample_size(power=0.8, alpha=alpha, effect_size=effect_size)

for _ in range(n_trials):

trial_result = run_monte_carlo_trial(mu_C=mu_C, mu_T=mu_T, N=N)

results.append(trial_result)

frame_alternative = pd.DataFrame(results)

(frame_alternative["p"] < alpha).mean()

The last line is the fraction of times that we get a stat-sig result. In the notebook, I get a result of 80.19%, which is very close to the expected 80% (the power)

Applying the simulations to the Bayesian Euro step

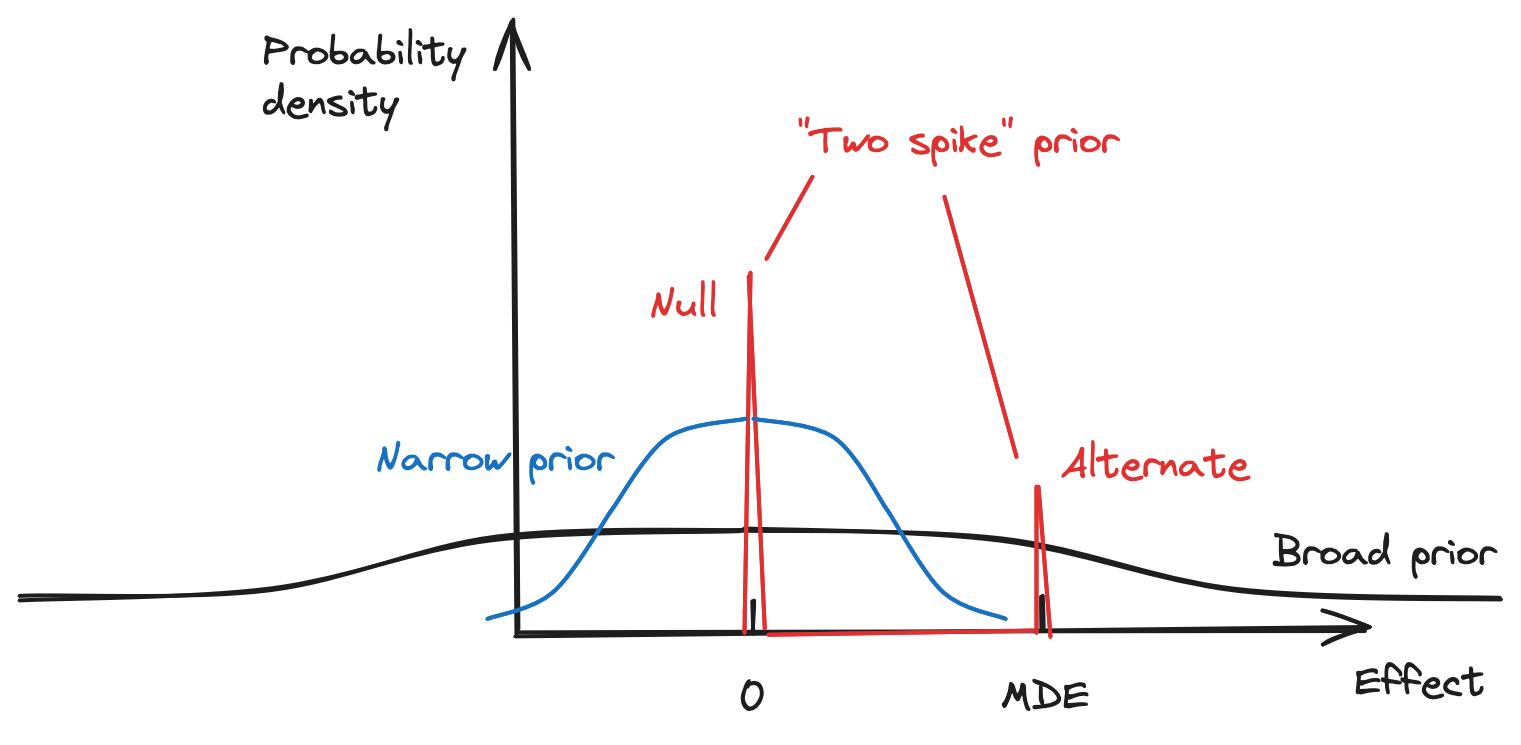

Now that we’ve confirmed the simulation is working as intended, let’s apply it to the Bayesian framework for interpreting A/B tests. We'll consider the three priors pictured schematically, below. (I'll explain what each of these are, in turn.)

First, let’s check Harlan Harris’s statement that, with a “broad” prior, obtaining a stat-sig result under NHST implies very strongly that the true effect is larger than 0.

To implement this, we set our prior as a Gaussian distribution with a standard deviation much larger than the minimum detectable effect (MDE), as pictured above.

n_trials = 10_000

results = []

effect_size = 0.05

mu_C = 1

N = gen_sample_size(power=0.8, alpha=0.05, effect_size=effect_size)

# note the "scale" (standard deviation of the prior) is much larger

# than the effect size we care about

# this is what a "broad" prior means

prior = rng.normal(loc=0, scale=1, size=n_trials)

for i in range(n_trials):

effect_size = prior[i]

mu_T = mu_C + effect_size

trial_result = run_monte_carlo_trial(mu_C=mu_C, mu_T=mu_T, N=N)

results.append({**trial_result, "effect_size": effect_size})

frame_broad = pd.DataFrame(results)

Then, we can calculate the probability that the true effect was greater than 0, given that the result was statistically significant.

(

frame_broad

# determine statistical significance (one-sided test)

.assign(stat_sig=lambda x: (x["p"] < 0.05) & (x["z"] > 0))

# limit to stat-sig results

.query("stat_sig")

.assign(true_positive_result=lambda x: x["effect_size"] > 0)

["true_positive_result"].mean()

)

I get an extremely large number: 99.95%. So, assuming a broad prior, it is extremely unlikely we are making a “type I error”: falsely assuming the effect was positive when it was actually neutral or negative.

At this point, though, you might notice something strange: the probability of a statistically significant result itself is very large. Out of the 10,000 trials we ran, close to 4950 (or, almost half) are statistically significant. In fact, this is not too surprising. Because the prior is so broad, if the effect is positive at all (which happens half the time), it is very likely to be large enough that it is statistically significant (again, assuming adequate power).

What if we choose a prior that is much less broad? We can repeat the calculation above with a "narrow" prior (again, see image above). Here, we'll set the standard deviation to 0.01 --- much less than the MDE. With this choice, the Monte Carlo simulations show that the “99.95%” number becomes “87%”. Now, there is a 13% chance we’re making a bad decision: much larger than the 2.5% that we’d originally thought from our value of "alpha" (dividing by two since we're doing a one-sided test). Also, the probability of a statistically significant result has gone down, from 49.5% to 4%.

What have we learned?

- Our results seem to have strong “sensitivity” to the prior: they depend a lot on what the prior is, and, in particular, how broad it is.

- It is hard to justify the assumption of a broad or “uninformative” prior. The results obviously depend on the prior; we cannot simply choose an arbitrary one. At the same time, the results for a broad prior do not agree with intuition either. It seems implausible that the true effect sizes are really as large as a broad prior implies, or that we should expect a statistically significant result close to half the time (for a one-sided test)

Somewhere along the way, we also lost the idea of the “null hypothesis”. This was always an abstraction (can the effect size really be exactly zero?), but let’s try to add it back in.

To do this, let’s combine NHST and Bayesian ideas. Instead of having the prior distribution be Gaussian, we have it be “two spikes”: one spike at 0, for the null hypothesis, and the other spike at the MDE, for the alternate hypothesis. (Again, see schematic above.) The distribution overall must have a probability mass of 1, so each spike will have a weight \(w \) \( (w_{null}, w_{alt}) \) that sums to 1.

So, our Monte Carlo simulation now looks like this:

# use more trials now, since one of the assignments might be rare

n_trials = 100_000

results = []

effect_size = 0.05

mu_C = 1

N = gen_sample_size(power=0.8, alpha=0.05, effect_size=effect_size)

# this is the prior probability of the null hypothesis, and can be changed

w_null = 0.9

w_alt = 1 - w_null

prior = rng.choice(a=['null', 'alternate'], p=[w_null, w_alt], size=n_trials)

for i in range(n_trials):

assignment = prior[i]

if assignment == "null":

mu_T = mu_C

else:

mu_T = mu_C + effect_size

trial_result = run_monte_carlo_trial(mu_C=mu_C, mu_T=mu_T, N=N)

results.append({**trial_result, "effect_size": effect_size, "assignment": assignment})

frame_two_spikes = pd.DataFrame(results)

We want to figure out the probability the null hypothesis is true, given we have a statistically significant result. This is the “inverse” probability we care about.

Here are the numbers I get for one run, with \(w_{null} \) ranging over the values 0.1, 0.5, and 0.9:

| P(null), prior | P(null | stat-sig result), posterior |

|---|---|

| 10% | 0.4% |

| 50% | 3% |

| 90% | 22% |

(It turns out that, for the two spike prior, you can use Bayes theorem directly and recover basically the same posterior probabilities. See here for more details.)

As the prior probability of the null hypothesis (the first column) increases, the probability of making a false positive judgment (the second column) also increases. The statement that “p < 0.05” means “95% likely to better” (assuming adequate power, etc.) is only true if the null hypothesis is not very likely. This also explains the results for the broad prior: it implicitly assumes the null hypothesis is not likely, and that large effects are commonly seen.

Interpretation and wrap-up

Traditional null hypothesis statistical testing (NHST) does not get us what we want: the probability the null hypothesis is true given a statistically significant result, or, in other words, the probability of making a “false positive” error. Instead, we get the opposite probability, which is often difficult to interpret

Using the Bayesian framework directly gives us the desired probability. This is a good thing!

However, the Bayesian framework introduces the concept/assumption of a prior. In the case of A/B tests, this is the prior distribution of the effect size, or, roughly equivalently, the prior probability that the null hypothesis is true. “Narrow” Gaussian prior distributions centered around 0, or large prior probabilities that the null hypothesis is true, are different ways of restating the same intuition: that the true effect is very likely close to 0. Similarly, a “broad” Gaussian prior distribution, where large effects are very likely, is equivalent to stating that the alternative hypothesis is reasonably likely (close to 50% for a one-sided test, or close to 100% for a two-sided test).

Regardless of how we want to frame it — in terms of prior probabilities for the null hypothesis, the scale of the effect size, or the variance of the prior distribution — we need some parameter that controls the prior. Our results end up being very sensitive to this quantity.

Recall that in the NHST world, we didn’t get the quantity we wanted. In the Bayesian world, we do, but we have to make a strong assumption — one which our results are highly sensitive to. (Again, no free lunch.) Bayesian reasoning makes assumptions explicit. But the assumptions are still there, nevertheless.

One clever approach for getting at this parameter is thinking about the probability of the null hypothesis. At large companies, we can do a “meta-analysis”, taking a large sample of adequately powered tests (since large companies typically run a lot of A/B tests). Then, we can compute the probability that the test was successful, and the null hypothesis was rejected. Ron Kohavi and others have done this, and they find that only ~10-15% of A/B tests, depending on the company, are successful. This figure implies that the probability of the null hypothesis should be somewhere around 85-90%. In other words, most of our ideas are either neutral or bad. (This fact can be hard to stomach, but it is generally true.)

(As an aside, one subtlety is in choosing the sample of A/B tests for the meta-analysis. Some tests might be more or less relevant to the test you have in mind, and focusing on a narrower sample of “more similar” A/B tests can be a good option.)

Given the assumption that only 10-15% of A/B tests are successful, the “false positive risk” — the probability the null hypothesis is true, given a statistically significant result — is ~15-22%, with 80% power and an alpha of 0.05. This is definitely much higher than the result you’d get from a “broad” Bayesian prior, as our analysis above showed.

Indeed, I feel that Bayesian A/B test interpretation that assumes a broad prior veers into the realm of bullshit. (This is like how the Bayesian Euro step can easily turn into “travelling”.) It is not enough to say “the prior is broad”; there has to be some meta-justification for this assumption. One case in which this assumption might be warranted is for certain types of A/B tests, where we are trying something new and there is a rough equivalence between treatment and control cells. (Harlan Harris calls these “agnostic” tests.) For example, choosing the color for a new button on a website. But these examples are rare and are certainly not representative of most A/B tests.

In most cases, I would advise either doing NHST with parameters even more restrictive than alpha = 0.05 and power = 80% (like Kohavi advises — e.g., alpha = 0.01 or 0.005), or doing the Bayesian Euro step with a prior probability of the null hypothesis of 85-90%, or perhaps a value you've obtained from your own meta-analysis on a sample of relevant experiments. Neither of these is equivalent to the broad prior, and the results obtained from that assumption will likely underestimate the actual “false positive risk” and overestimate the actual effects.